By Amir Rashad Mustaffa

According to William Shakespeare, “what is past is prologue”. This serves as a poignant reminder that history lays the foundation for what lies ahead. Just as students around the world study Shakespeare and Chaucer to understand the evolution of English thought, culture, and language, so too should Malaysians turn to the literary and linguistic treasures of Old and Classical Malay.

Now in an age where we are zooming forward with technology, globalisation, and modern language trends rapidly reshaping the way Malaysians communicate, there is an urgent need to look in retrospect, reflect on the roots of our national language, and reconnect to our past. Revisiting the inscriptions of Old Malay and the rich manuscripts of Classical Malay is not merely an academic exercise; it is a crucial step toward preserving and understanding Malaysia’s cultural identity. By re-engaging with these earlier forms of Malay, we not only honour our heritage but also ensure that future generations inherit a language anchored in history and meaning.

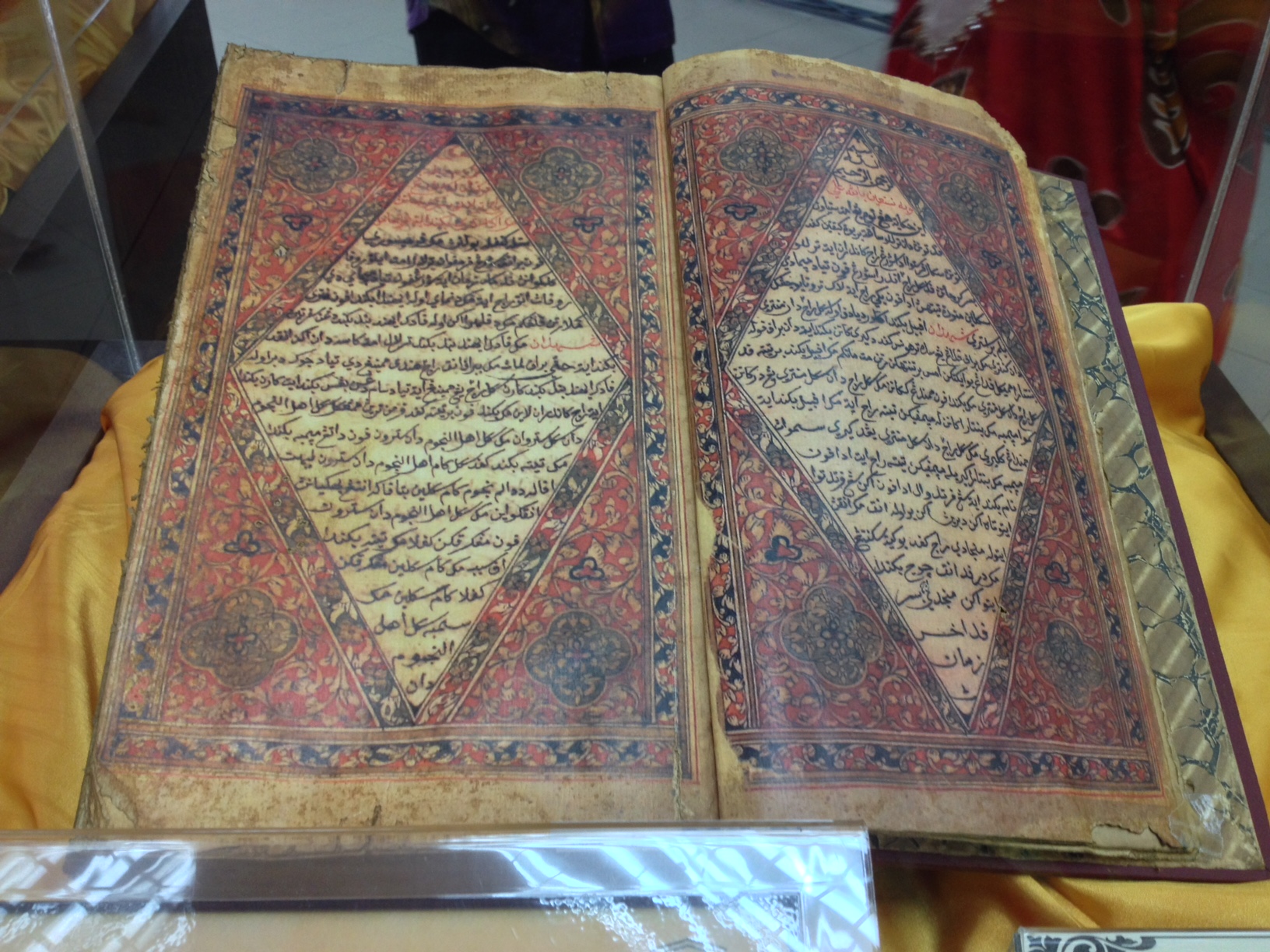

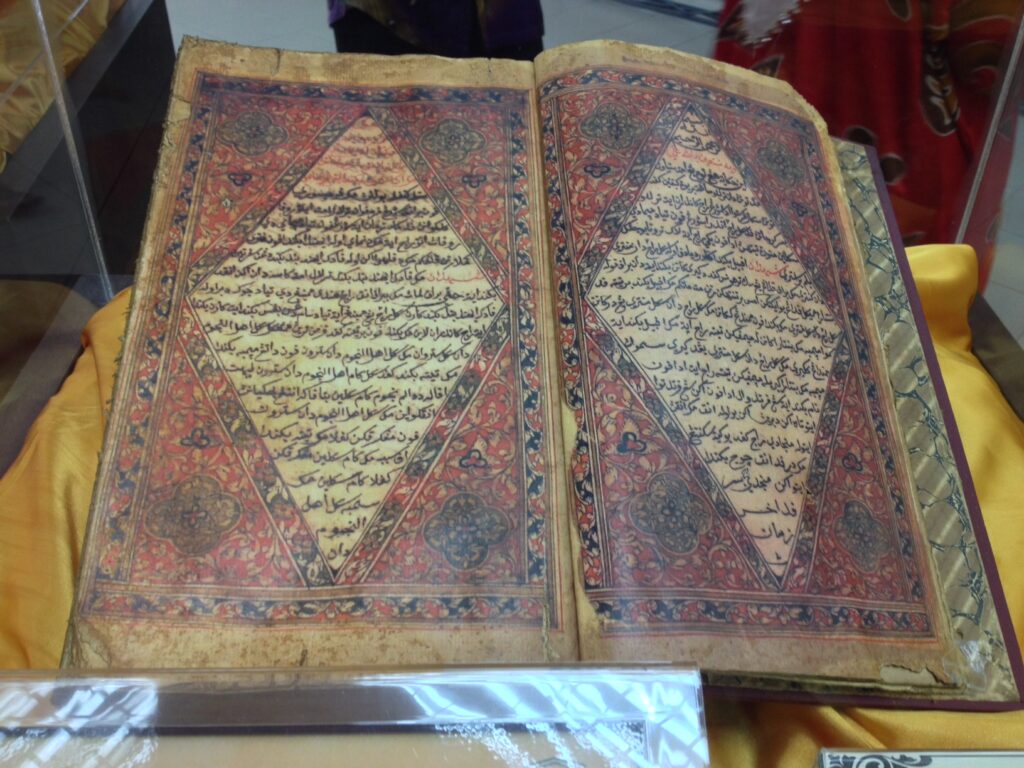

Old and Classical Malay, found in inscriptions or manuscripts dating as far back as the 7th century and flourishing during the height of the Sultanate of Melaka circa the 15th century, serve as the linguistic fingerprints of our civilisation. These historical forms of Malay are not just predecessors of the language that we speak today, but are the repositories of our shared knowledge as inhabitants of the beautiful land we now lovingly know as Malaysia. Each text, whether engraved in stone like the Old Malay Telaga Batu inscription, written on tree bark like the Old Malay Tanjung Tanah manuscript, or copied in Jawi script like the Classical Malay hikayat, offers clues about how our ancestors thought, governed, traded, and worshipped. This is not just language; it is memory carved into time.

Understanding the language that our ancestors had once spoken reveals how it evolved over centuries. It provides a map of historical contact with Sanskrit, Arabic, and later, Portuguese and Dutch influences, among others. Through it, we learn how Malay society adapted foreign concepts into its own lexicon and worldview without losing its identity. For instance, the shift from Sanskrit-influenced Old Malay to Arabic-influenced Classical Malay shows not only linguistic evolution, but also the religious and intellectual transformation of the region. Words such as budi and derma from Sanskrit, as well as hikmat and adab from Arabic, carried nuanced meanings that informed the values of belief, governance, education, and conduct for centuries.

The National Language Act rightly prioritises Bahasa Melayu as a symbol of unity. However, this symbol is only as strong as the foundation it rests on. A deeper knowledge of Old and Classical Malay, poetic forms like pantun and syair, and legal documents like Undang-Undang Melaka can enrich our appreciation of the language we speak today. More importantly, reinvigorating interest in Old and Classical Malay can inspire a new generation of Malaysians to take pride in their linguistic heritage. At a time when young people are rapidly absorbing global pop culture, studying our ancient texts can re-anchor us in local wisdom and identity.

Unfortunately, the study of what we might even call the Malay classics is often confined to the ivory tower or perceived as niche. We need greater integration of classical texts and linguistic history in school curricula, museums, and digital platforms. For example, by digitising, translating, and popularising these texts, as done by Dr. Annabel Teh Gallop from the British Library, we can allow for greater reach and access to these materials. Let students interact with Hikayat Hang Tuah not just as a story, but as a lesson in how our ancestors used metaphors, allegory, and high-register Malay to express complex emotions and ideas.

As Malaysia continues to define itself on the global stage, understanding the linguistic architecture of Old and Classical Malay reminds us of who we are, where we come from, and what we must protect. Our language is not just a tool for daily conversation; it is a living legacy that binds us to the past and guides us into the future.

Studying the classical forms of Malay is not about nostalgia. It is about reclaiming intellectual sovereignty, deepening cultural understanding, and passing on to future generations, the rich inheritance of the land we call home. The land speaks through stone, manuscript, and rhyme. It is time we listen!

Dr. Amir Rashad Mustaffa is a Senior Lecturer at the Department of Malaysian Languages and Applied Linguistics, Faculty of Languages and Linguistics, Universiti Malaya