By Xu Yiren, Yuan Zilu, Dr Mohd Istajib Mokhtar

In our increasingly digitised world, technology is not just a convenience — it has become essential to communication, learning, work, and civic participation. Yet, while some people navigate digital spaces with ease, many others remain sidelined. This disparity, known as the digital divide, is no longer just about access to devices or the internet. It includes gaps in digital literacy, economic power, and control over advanced technologies like artificial intelligence (AI).

Dutch media scholar Jan van Dijk has long argued that the digital divide spans three dimensions: access, skills, and control. His theory remains relevant as we see deepening inequalities in who can use, benefit from, and shape digital technologies. This article examines the digital divide at three levels — individual, enterprise, and global — and reflects on how ethical frameworks can help close the gaps.

While teenagers master TikTok and digital natives switch between multiple platforms, many older adults struggle just to get online. In the U.S., for instance, nearly one in four adults over 65 still do not use the internet, according to a 2022 report by Monica Faverio at the Pew Research Center.

This disconnection isn’t just inconvenient — it’s isolating. As public services move online and community life shifts to digital spaces, many older people are excluded from essential resources and public discourse.

From an ethical perspective, particularly through the lens of media ethics, this exclusion violates principles of equal access to information and freedom of expression. If digital platforms serve as modern public squares, then denying seniors entry undermines democratic participation. The solution? Expand targeted digital literacy programmes in community centres, schools, and elder care facilities to equip all age groups to navigate digital society.

The enterprise level: small businesses at a disadvantage

The digital divide isn’t just a personal issue — it affects businesses, too. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) often lack the resources and expertise to compete with corporate giants who dominate online spaces using data analytics and advanced digital tools.

Researchers Qi Li, Weijie Tian, and Hong Zhang have shown how this imbalance limits the ability of SMEs to optimise supply chains and engage customers in a digital economy. Larger firms can afford to invest in high-end platforms, while smaller ones fall behind, unable to reach audiences or scale their services.

From the standpoint of communication ethics, this is a question of fairness. Every business deserves a chance to tell its story and reach its audience. Policy efforts like the European Union’s Digital Services Act (DSA) aim to level the playing field by requiring algorithmic transparency and better protections for small enterprises.

But legislation alone isn’t enough. Governments and tech companies must provide accessible digital infrastructure, offer affordable training, and monitor how platform algorithms impact smaller players.

The global level: algorithmic bias and power asymmetries

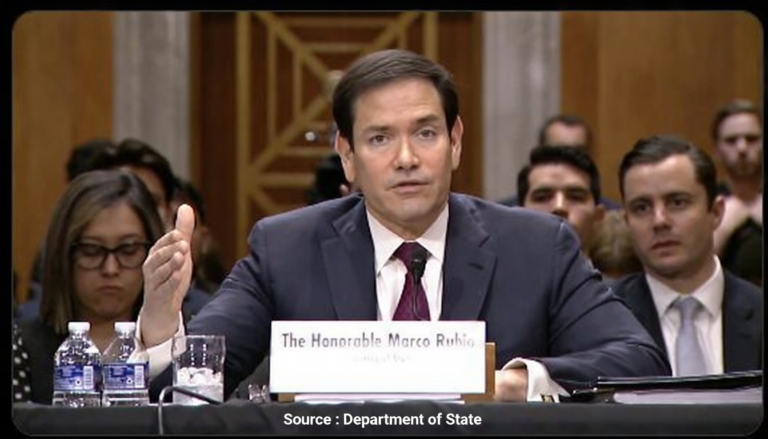

The most complex layer of the digital divide is the global divide in AI governance. Today, a small number of countries and corporations dominate the creation and deployment of AI systems — especially those that control social media algorithms.

A recent study by Mohammed Y. Mohammed and colleagues examined how algorithms shaped coverage of the Israeli-Gaza conflict. They found that automated content delivery systems can reinforce certain political narratives while downplaying others, influencing how global audiences perceive complex issues.

This raises serious concerns under AI ethics. If only a handful of powerful actors develop these systems, whose voices get heard? And whose are silenced? This imbalance in algorithmic control mirrors old forms of colonialism, where power is concentrated and representation is skewed.

To bridge this divide, we need global cooperation on AI governance, inclusive datasets, and transparent algorithms that reflect the diversity of the world they serve. Tech giants must be held accountable, not just for innovation, but for equity.

Bridging the divide

Closing the digital divide requires more than new gadgets or faster internet — it calls for ethical leadership and systemic change. Education must be reimagined to treat digital literacy as a basic right, equipping all individuals not only with skills, but with the critical thinking needed to navigate an ever-evolving digital landscape.

Governments should support small businesses by enforcing fair digital policies and offering training programmes that help SMEs compete on equal footing. Ethical communication requires that every enterprise, regardless of size, can share its story.

At the technological level, algorithmic accountability must become standard. This means auditing AI systems for bias, designing with inclusive data, and ensuring that platforms prioritise fairness and transparency over mere engagement metrics.

And on the global front, we must push for international cooperation and solidarity to ensure that no community is excluded from the AI revolution. Global regulation must guard against technological monopolies and give developing nations a seat at the digital table.

More than a decade ago, Van Dijk warned that digital inequality could become a lasting social fracture. Today, that risk is real. The responsibility lies with all of us — policymakers, educators, developers, and everyday users — to bridge the digital divide with inclusion, fairness, and ethics at heart.

Toward a fairer digital future

The digital divide isn’t just about who has Wi-Fi. It’s about who gets to speak, who gets heard, and who gets left behind. Whether it’s an older adult struggling with online banking, a local shop drowned out by corporate advertising, or an entire country marginalised by AI algorithms, the issue cuts across every layer of modern life.

Ethical reflection is not a luxury — it’s a necessity. By embracing the principles of media ethics, communication fairness, and algorithmic justice, we can shape a digital world that works for everyone, not just the connected few. Because a truly digital society must also be a just one.

The authors are from the Department of Science and Technology Studies, Faculty of Science, Universiti Malaya