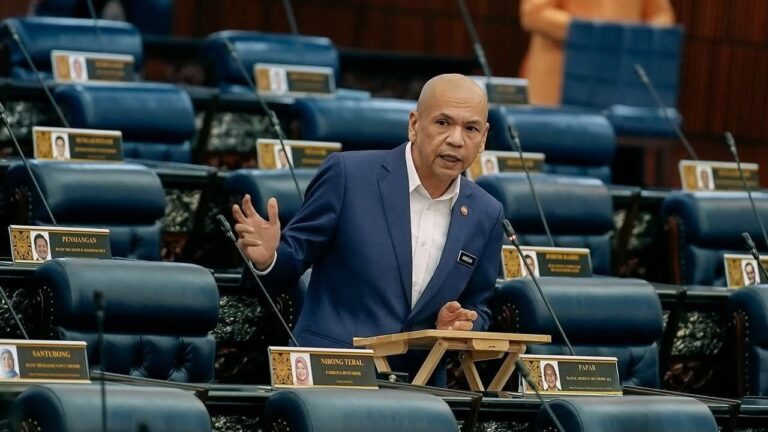

By Haezreena Begum Abdul Hamid

The integrity of a nation’s border is fundamental to its sovereignty, security, and reputation. In Malaysia, however, recent revelations have highlighted troubling systemic vulnerabilities within immigration and border enforcement practices particularly through covert and corrupt mechanisms known as “passport terbang” and “counter-setting.” These practices not only compromise lawful migration processes but also facilitate serious transnational crimes, including human trafficking and the smuggling of migrants.

“Flying passport” (or ‘pasport terbang’ in Malay) refers to the unauthorised practice of submitting a passport to immigration authorities for renewal, visa endorsement, or extension without the physical presence of the passport holder. This contravenes official procedures which mandate in-person attendance for identity verification, often through biometric means. In many of these cases, passports are collected and transported by intermediaries on behalf of the holder in exchange for illicit fees.

Counter-setting, on the other hand, involves immigration officers at entry or exit points such as Kuala Lumpur International Airport intentionally manning specific counters to facilitate the unlawful passage of foreign nationals without proper documentation or scrutiny. These activities are typically arranged through clandestine networks and are executed in exchange for bribes.

Though seemingly procedural deviations, both practices signify entrenched corruption within parts of the immigration system, threatening not only Malaysia’s border control efficacy but also the country’s international standing in law enforcement, anti-trafficking efforts, and governance.

A critical enabler of these corrupt practices is the role played by a wide range of intermediaries including employment agents, taxi drivers, freelance “runners,” and even certain members of airport staff. In trafficking-related cases, passports belonging to victims are often seized by traffickers and handed to these intermediaries, who in turn bribe immigration personnel to process renewals or extensions without the victim’s awareness or consent. This shadow network enables the formal legalisation of an illegal or exploitative presence, allowing trafficked persons to remain in the country with official documentation while being subjected to labour or sexual exploitation. Victims are thus rendered invisible to protective institutions, as their legal status on paper conceals the coercion and abuse they endure in practice.

These practices raise pressing legal and policy concerns because they violate several laws such as Section 55E of the Immigration Act 1959/63, which criminalises harbouring or employing undocumented migrants. It also contravene the Anti-Trafficking in Persons and Anti-Smuggling of Migrants Act 2007, particularly where visa fraud is used to facilitate continued exploitation.

In addition, these practices undermine the standard operating procedures of the Immigration Department which mandate physical presence and biometric identity confirmation, and risk compromising Malaysia’s compliance with international legal instruments, including the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC) and the UN Trafficking Protocol. Moreover, these practices significantly erode public confidence in enforcement agencies, perpetuate a culture of impunity, and hinder the nation’s efforts to combat organised crime and protect vulnerable populations.

To address these challenges, a multipronged strategy is required which targets both systemic weaknesses and individual accountability such as mandating biometric and in-person verification for all immigration procedures. First, strict enforcement of in-person biometric verification for all passport, visa, and permit applications. Digital systems should automatically flag and suspend applications submitted without such verification.

Second, implement real-time surveillance and tamper-proof digital logs. In this instance, it would be useful to install CCTV with live monitoring at immigration counters and visa-processing units. All entry and visa transactions should be recorded in tamper-proof systems accessible only to authorised personnel, with audit trails built in.

Third, identify, blacklist, and prosecute facilitators and middlemen involved in these activities. In this instance, it is recommended to maintain a registry of blacklisted intermediaries suspected or convicted of engaging in corrupt immigration practices.

Fourth, enforcement action should extend to all parties involved including agents, syndicates, and complicit civilians.

Fifth, enforcement of a system of regular staff rotations across immigration offices and entry points to disrupt entrenched corrupt networks and prevent collusion between officers and external actors.

Sixth, strengthen awareness among foreign nationals who are residing or working in Malaysia. They should be educated on lawful immigration procedures, the risks of using unauthorised intermediaries, and the legal consequences of engaging in document fraud. Multilingual outreach materials should also be made readily available.

Flying passport and counter-setting are not mere administrative lapses but are manifestations of systemic corruption that threaten the rule of law, embolden transnational crime, and endanger human security. Malaysia’s commitment to border integrity must be matched by the political will to root out these practices and strengthen the accountability of its immigration enforcement framework.

Just as immigration officers are duty-bound to uphold the law, foreign nationals must also respect and comply with Malaysia’s immigration regulations. Any attempt to bypass due process whether through bribery, fraud, or intermediary collusion undermines the legitimacy of the nation’s legal system and puts both individuals and the broader public at risk.

Malaysia stands at a critical juncture: ensuring that its borders are not only efficient and accessible but also just, secure, and corruption-free.

Dr. Haezreena Begum Abdul Hamid is a Criminologist and Senior Lecturer at the Faculty of Law, University of Malaya.