Why collective action is our only way forward

By Sabri Sulaiman

School violence in Malaysia is showing worrying signs of escalation, raising serious concerns among policymakers, parents, and educators about the emotional well-being and safety of our children. From verbal abuse and bullying to physical assault and cyberbullying, this issue is rapidly becoming a pressing social problem that demands our immediate collective attention.

School violence, defined as violent acts occurring in the school setting—whether on school property, during the commute, or at a school-sponsored event—disrupts learning and negatively affects students, the broader community, and our educational institutions. Examples of this violence include fighting, bullying, gang violence, cyberbullying, weapon use, and sexual violence.

Recent tragedies have laid bare the fragility of safety in our institutions. We have witnessed a tragic series of incidents, including a gang rape in Malacca, increasing cases of school bullying, and the murder of a 16-year-old student by a 14-year-old schoolmate. These events force us to question whether our schools are truly safe havens for children.

The data confirms this crisis. A recent Ministry of Education report reveals that cases of violence in schools have risen drastically: from 3,883 cases in 2022, they jumped to 6,528 cases in 2023, and reached 7,681 cases in 2024. These numbers are alarming. Schools are intended to be safe environments where children develop their psychological and social skills, learn, and play. Yet, teachers and counsellors are concerned that students increasingly resort to aggression to resolve conflicts, often influenced by environmental pressures, peer pressure, domestic stress, and exposure to social media.

From a sociological perspective, aggressive or violent behaviour among students is multifactorial. Factors include the bully’s own personal issues, such as a need for power, lack of empathy, anger issues, or low self-esteem. Crucially, behaviour is also shaped by environmental factors, including witnessing bullying and violence, a dysfunctional home life, domestic violence, or a lack of parental supervision. We also know that individuals are sometimes victimised simply for being perceived as different, whether due to disability, physical appearance, religion, race, or sexuality.

It is my firm conviction that schools cannot handle this issue alone. We must adopt a comprehensive and collective approach involving all communities as a primary initiative. Collective action necessitates coordinated efforts from civil society, governments, parents, students, teachers, and education officials to foster safe learning environments. Solutions require an “all-of-society approach” that addresses the root causes of violence, implements clear policies, and fosters a robust culture of safety, rather than relying on reactive measures or quick fixes. This includes involving youth in developing solutions, and fostering intergenerational collaboration and local and international partnerships.

While Malaysia has introduced commendable efforts, such as the Sekolahku Sejahtera framework, which promotes shared responsibility, holistic well-being, and character development in schools, I believe stronger psychosocial support systems are still desperately needed. This is especially true in schools serving low-income or high-risk communities. We must integrate mental health education and social and emotional learning (SEL) into our school curricula. Such programmes can effectively teach students empathy, self-control, and non-violent conflict resolution, thereby helping to build resilience and positive peer relationships.

Furthermore, community-based programmes for school violence prevention play a crucial role. They provide young people with safe spaces to engage in positive activities and express themselves. These programmes, which often partner with community organizations to offer comprehensive support, must focus on social norms, skills, and the environment. Strategies should include improving school and community environments through urban planning; training staff, parents, and students; teaching essential social-emotional skills like self-awareness and problem-solving; and actively building positive peer relationships.

We also cannot ignore the role of the digital sphere. Exposure to violent content, online bullying, and toxic digital culture has the capacity to normalise aggression among adolescents. Therefore, digital literacy education must move beyond merely teaching how to operate technology; it must teach students how to navigate the digital landscape ethically and safely.

Ultimately, the fight against school violence is a direct reflection of our nation’s broader commitment to social justice and social care. Protecting every child’s right to learn in a safe, nurturing environment is not simply a school matter—it is a societal duty.

As I have often stressed, “Children learn what they live”. If they mature in environments where care, respect, and empathy are standard practice, they will inevitably carry those values into their communities and schools. Conversely, if violence becomes normalised in their daily lives, the destructive cycle will continue.

As Malaysia works to establish a more inclusive and compassionate society, ensuring safe schools must remain at the heart of our community action and national policy. Every act of violence in school is not merely a disciplinary issue; it is a critical warning sign of deeper social fractures that demand coordinated response, care, and understanding.

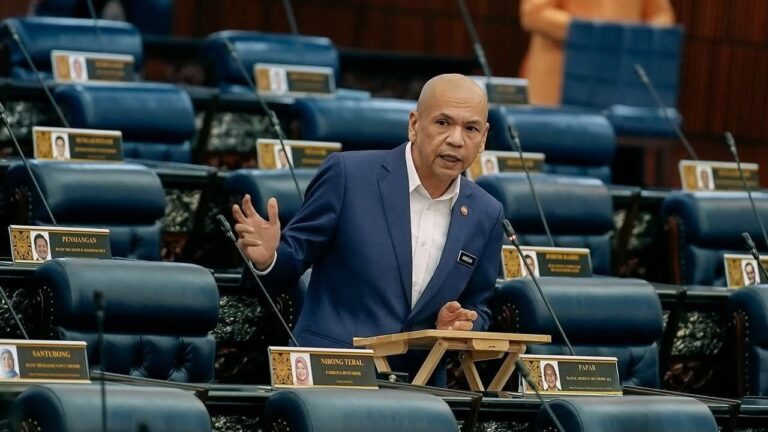

Dr Sabri Sulaiman is a Senior Lecturer at the Department of Anthropology and Sociology, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Universiti Malaya,