By Nahrizul Adib Kadri

There’s a phrase many of us struggle to say out loud: “I don’t know.”

In boardrooms, classrooms, and even family conversations, the pressure is often to have answers ready, to project confidence, to leave no space for doubt. We reward those who sound certain, even when certainty is little more than a polished guess. The hesitation, the pause, the quiet admission of not knowing are often seen as weaknesses to be hidden.

But what if we have misunderstood the value of ignorance?

I don’t mean ignorance in the sense of intentionally being ‘blind’, refusing to learn or shutting down what we do not want to see. I mean the honest, vulnerable admission that there are things we have not yet grasped. The kind of ignorance that, when acknowledged, can become the first step towards something profound.

“I don’t know” is not the end of the road. It is the opening of one.

I have written before about the importance of asking the right questions, and about the humbling truth that we will never understand everything. This is slightly different. This is about giving dignity to uncertainty itself. It is about recognising that the strength to admit what we do not know is, in many ways, the beginning of wisdom.

Carl Sagan once said, “Somewhere, something incredible is waiting to be known.” That “something” can only be found when we leave space for it, when we admit the gap between what we know and what we do not. Curiosity needs room to breathe, and that room is carved out every time we confess our ignorance.

Think about the times in your own life when you have learned most deeply. Chances are, they did not begin with certainty. They began with discomfort. With a question that did not have an easy answer. With the moment you said, “I don’t know how to do this… yet.”

That little word ‘yet’ is very important. It transforms “I don’t know” from a dead end into a doorway.

In our culture of fast takes, instant expertise, and viral soundbites, we have become allergic to the pause. We see leaders fumbling for answers and call it weakness. We see students unsure of themselves and rush to fill the silence. Yet there is quiet power in letting that pause stretch. In resisting the temptation to pretend.

And when we acknowledge ignorance, three things happen. First, we disarm arrogance. There is no need to pretend we have mastered what we have not. This humility builds trust. Nobody believes someone who claims to know everything. Most of us, however, can respect the person who says, “That’s not clear to me. Let’s find out together.”

Second, we invite collaboration. Admitting not knowing is an open door to others. It creates space for shared learning, for multiple perspectives, for growth that does not rely on one loud voice carrying the room.

And thirdly, we give ourselves permission to grow. Pretending we already know keeps us stagnant. Admitting we do not know positions us as learners, no matter our age or title.

History gives us countless examples of this. The great scientists, philosophers, and thinkers did not begin by claiming certainty. They began with doubt. Marie Curie, standing in her lab, did not know what radiation would reveal. Einstein, staring at the limits of Newton’s laws, admitted he did not know what accounted for Mercury’s wobble until he asked a new question. In Plato’s “Apology,” Socrates says, “For I was conscious that I knew practically nothing,” and he often expressed the view that his wisdom was to know the limits of his own knowledge.

This is not weakness. It is courage.

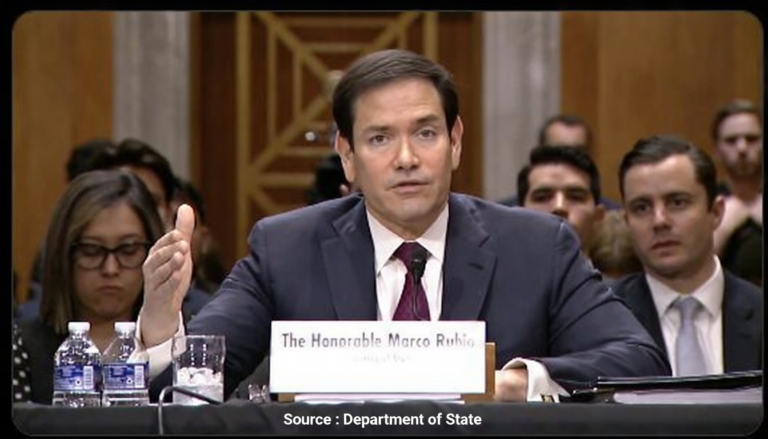

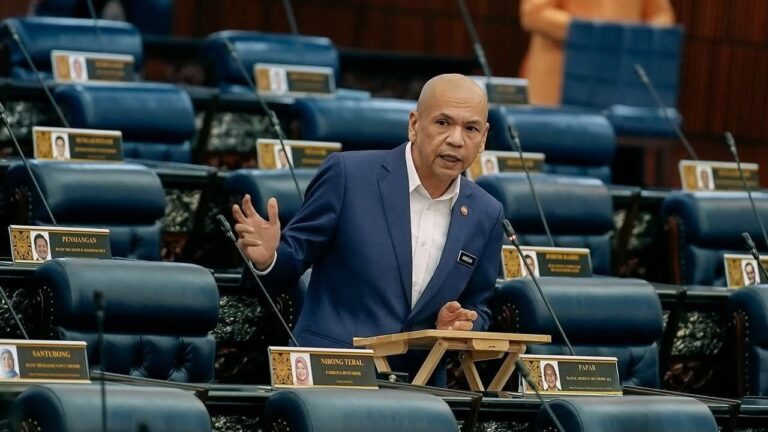

Perhaps it is something we need more of in Malaysia too. As a society, we often look to our leaders for instant answers. We expect policies to be rolled out without hesitation, reforms to be perfectly planned, visions to be flawlessly executed. Yet nation-building, like personal growth, is full of unknowns. To admit this, that we do not yet know all the solutions to national unity, climate change, inequality in education, corruption, or governance, is not to admit defeat. It is to acknowledge reality and in doing so to leave space for new ways forward.

What worries me more than “I don’t know” is the loud, unshakable insistence of those who claim they already do. That kind of certainty leaves no room for dialogue, imagination, or change.

So perhaps as this Merdeka season comes to an end, as we reflect on how far we have come and how much we still have to learn as a nation, I invite you to cultivate the quiet courage of saying “I don’t know.”

Say it without shame. Say it without fear. Say it as a declaration of curiosity, of openness, of readiness to learn. Because “I don’t know” is not weakness. It is soil. And from it, understanding can grow.

After all, somewhere, something incredible is waiting.

Ir Dr Nahrizul Adib Kadri is a professor of biomedical engineering at the Faculty of Engineering, and the Principal of Ibnu Sina Residential College, Universiti Malaya.