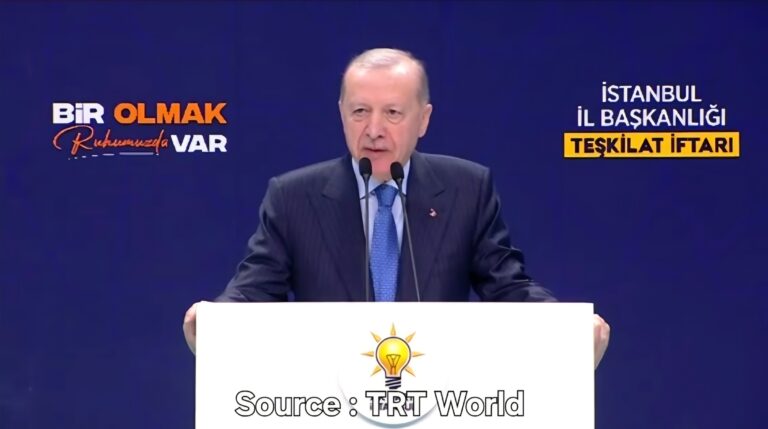

Malaysia’s Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim posts a solitary “.” with this image on Facebook after the ASEAN Summit. (Photo: Anwar’ FB)

By: Abdullah Bugis

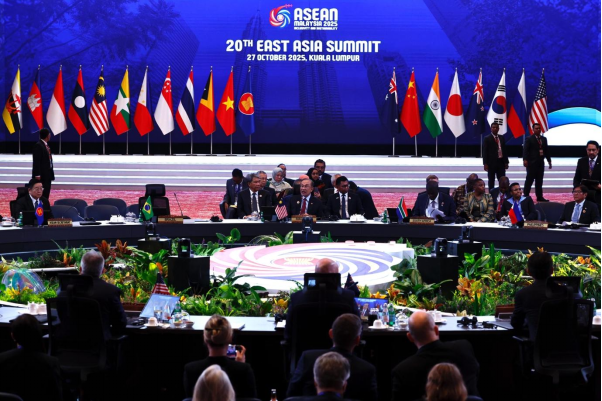

In the quiet moments following the closure of the the 47th Summit of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN )and Related Summits, Malaysia’s Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim posted a single punctuation mark “.” on his official Facebook account. The post was minimalist yet powerful: a single full stop, standing alone beneath Anwar Ibrahim’s official account. Without a caption or context, it conveyed the quiet that follows diplomatic whirlwind — a reflective pause after three intense days in Kuala Lumpur, where over thirty world leaders gathered from 26 to 28 October 2025 under the banner of “Inclusivity and Sustainability.” As host nation and Chair of ASEAN 2025, Malaysia had placed itself at the center of global attention, redefining the bloc’s role amid fractured geopolitics and deepening protectionist currents.

From United States President Donald Trump and Chinese Premier Li Qiang, to Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, and United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres — power and politics filled Malaysia’s capital. Alongside them, the leaders of all eleven ASEAN nations, including the newly admitted Timor-Leste. The summit’s outcomes signaled both ambition and anxiety: a region trying to shape the rules of geopolitics while avoiding being ruled by them.

America, Tariffs, Peace, Strategy

The summit’s most unforgettable image came not from the plenary hall but from the tarmac of Kuala Lumpur International Airport. The moment Trump stepped off Air Force One, the theme music of Hawaii Five-O filled the air. Trump executed his familiar campaign-trail dance move, and Anwar, breaking diplomatic stiffness, joined him briefly. Cameras flashed. The world watched. Critics mocked; supporters celebrated. But symbolism quickly evolved into strategy.

Inside “The Beast” — the presidential armored limousine, Trump and Anwar held a private, unscripted exchange before heading toward the summit venue. Hours later, the United States formally witnessed the signing of the Kuala Lumpur Peace Accord between Cambodia and Thailand. The accord turned the July ceasefire into enforceable commitments: withdrawal of heavy weapons, deployment of ASEAN monitors including Malaysians, and the release of 18 Cambodian prisoners of war. Both Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Manet and Thai Prime Minister Anutin Charnvirakul praised Washington’s pressure and Malaysia’s mediation for transforming conflict into cooperation.

Economics soon shared the stage with peace. Malaysia and the U.S. announced the elevation of bilateral ties to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, accompanied by a trade agreement and a Memorandum of Understanding on critical minerals and rare-earth elements. Tariffs on Malaysian exports would remain at 19 percent, while Washington guaranteed continued tariff exemptions for Malaysian semiconductors and electronic components — the backbone of the country’s industrial exports. Meanwhile, U.S. purchasing commitments included aircraft from Boeing, liquefied natural gas (LNG), and high-end data center components, reflecting Malaysia’s integration into American supply-chain strategy.

Yet domestically, the long shadows of sovereignty were cast. Opposition MP Wan Ahmad Faisal Wan Ahmad Kamal denounced the agreement as a “devil’s deal”, claiming it surrendered Malaysia’s strategic minerals to U.S. control and citing the red-carpet dance as emblematic of negotiation imbalance. In rebuttal, Malaysia’s Minister of Investment, Trade and Industry Tengku Zafrul Aziz insisted no government funds were mandated, and that any rare-earth exports to the U.S. must first undergo value-added processing in Malaysia, safeguarding national industrialization.

Thus, Kuala Lumpur became a stage where political theater met geopolitical calculus… and where ASEAN’s struggle to balance U.S. security with economic autonomy was laid bare.

Gaza, Myanmar, Regional Conscience

The summit was not merely transactional; it carried moral weight. In Kuala Lumpur, Anwar reaffirmed support for Trump’s 20-point Gaza peace plan, calling it “a glimmer of hope.” But he stressed the necessity of Palestinian statehood — a foundational element missing from Washington’s draft. Anwar reiterated this position during the East Asia Summit. While the U.S. prioritized ceasefire mechanics, Malaysia reminded that peace without justice is a temporary pause, not a solution.

Security around Trump’s visit was tight, as small pro-Gaza protests unfolded in Kuala Lumpur, a reminder that Malaysian diplomacy is closely watched by its own citizens and the wider Muslim world.

On Myanmar, ASEAN recommitted, once again, to the Five-Point Consensus adopted in 2021: ending violence, initiating dialogue, and delivering humanitarian aid. Anwar recounted his direct communication with Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, urging reduced attacks in Karen and Rakhine States. Although some villages saw fewer burnings this year, ethnic persecution — particularly against Rohingya — continues to expose ASEAN’s limitations.

Sudan surfaced in discussions through warnings raised by U.N. Secretary-General Guterres, who pointed to the worsening violence in Al-Fashir and global economic inequality exacerbating conflict. For ASEAN, his message was clear: wars beyond Southeast Asia distort supply chains, fuel refugee flows, and pressure humanitarian capacities at home.

Thus, ASEAN asserted a regional conscience, but its capacity to influence outcomes in Gaza or Myanmar remains to be proven.

China Trade, Sea Stability

A major economic milestone came with the signing of the upgraded ASEAN-China Free Trade Area Version 3.0 (ACFTA 3.0), expanding collaboration into the green economy, digital trade, consumer protection, fair competition, and SME empowerment. With China serving as ASEAN’s largest trading partner for 16 consecutive years, the upgraded pact aims to preserve growth while reducing logistical and regulatory friction.

Geopolitical fault lines remained visible. Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. vowed that as ASEAN Chair in 2026, Manila would push for a binding South China Sea Code of Conduct, citing “dangerous coercive actions” that threaten UNCLOS maritime freedoms. China’s Premier Li Qiang responded with caution: cooperation yes, confrontation no — warning against the “securitization of economic policy.”

Amid this, Malaysia emphasized multi-lateral naval drills and de-escalation mechanisms. Anwar spoke of the South China Sea as a “corridor of prosperity, not a theatre of conflict.”

Complementing this security vision, Kuala Lumpur hosted the 5th RCEP Leaders’ Summit, reminding the world that ASEAN stands at the center of the largest free-trade pact globally — representing about one-third of global GDP and binding ASEAN more tightly to China, Japan, Korea, Australia, and New Zealand. RCEP’s review is scheduled for 2027, signaling long-term commitment to open economic architecture despite growing protectionism elsewhere.

Prosperity and peace are not parallel tracks — they are the same road.

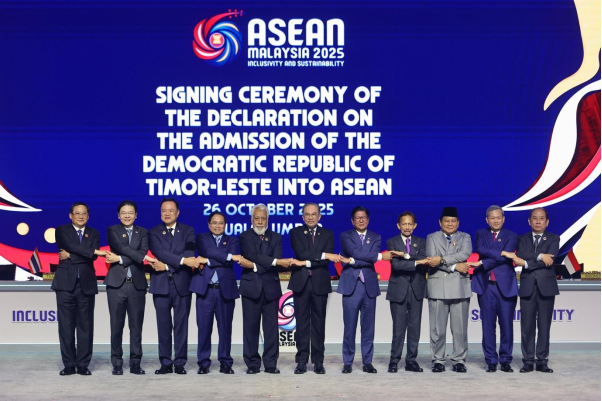

Timor-Leste Joins ASEAN

History was written at the summit’s opening: Timor-Leste became ASEAN’s eleventh full member — its first expansion since the late 1990s. Prime Minister Xanana Gusmão described the accession as “the fulfillment of our democratic journey,” concluding the nation’s long bid since 2011.

With only 1.4 million citizens, Timor-Leste gains access to ASEAN’s collective market, regional connectivity infrastructure, and multilateral security frameworks. ASEAN Secretary-General Kao Kim Hourn emphasized that membership amplifies Dili’s global diplomatic voice, while Anwar called the moment “the completion of the ASEAN family.”

Yet, challenges accompany celebration: capacity building, regulatory alignment, institutional reforms — all required to ensure accession is transformational, not merely symbolic.

Summit Meaning and Momentum

Malaysia’s chairmanship proved far more than a ceremonial showcase; with 80 adopted outcome documents, the summit positioned ASEAN at the heart of an ongoing Indo-Pacific realignment. Kuala Lumpur delivered a landmark peace accord in mainland Southeast Asia, redefined economic ties with the United States, strengthened the trade and supply-chain framework with China, and oversaw the historic formal admission of Timor-Leste as the bloc’s 11th member — all signaling a region intent on shaping, rather than merely observing, the geopolitical shifts around it.

And beneath the political headlines, a quiet economic signal: the Malaysian ringgit strengthened modestly against the U.S. dollar in the days following the summit, reflecting market confidence that Malaysia’s global diplomacy may reinforce domestic economic recovery — though analysts await sustained momentum.

As Malaysia prepares to pass the ASEAN chairmanship gavel to the Philippines for 2026, the true legacy of Kuala Lumpur will not be judged by announcements made on stage, but by the results that follow. The coming year will reveal whether the Kuala Lumpur Peace Accord can sustain calm along the Thai-Cambodian border, and whether ACFTA 3.0 and progress under RCEP can translate into fairer market opportunities across the region. It will also test if the newly expanded U.S.–Malaysia economic arrangements can withstand parliamentary scrutiny and public skepticism at home. Meanwhile, global expectations will focus on whether ASEAN can move beyond rhetorical concern to tangible influence on the crises in Gaza and Myanmar. And finally, ASEAN must demonstrate that welcoming Timor-Leste as its eleventh member is an act of empowerment and integration—not symbolic inclusion that leaves the youngest member on the sidelines.

Anwar’s solitary “.” did not signify an ending — but a pause before commitments are converted into consequences. Kuala Lumpur reminded the world that ASEAN is no longer content to be a passive arena of great-power rivalry. It intends to shape the future, not merely endure it.

Whether this summit becomes a turning point or just another pause in global diplomacy will depend on how Southeast Asia writes the next sentence after that dot.